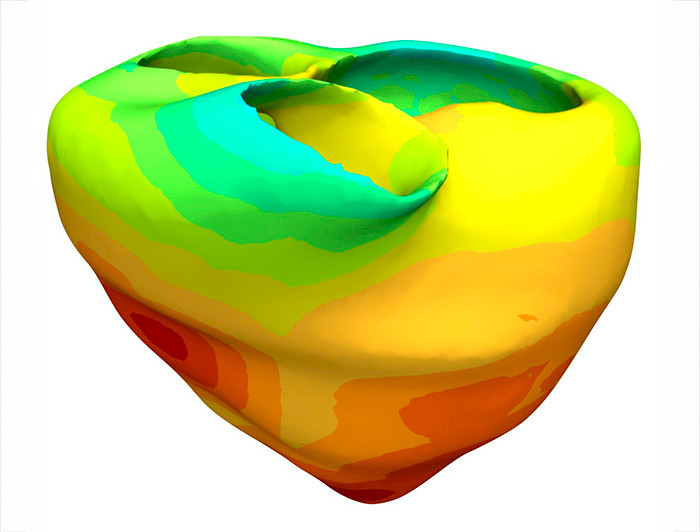

Innovative Heart ‘Digital Twin’ Could Transform Cardiac Disease Treatment

Using artificial intelligence, Francisco Sahli, professor of engineering and researcher at iHealth, has developed a pioneering computational model that digitally reconstructs the heart’s electrical conduction system from a standard electrocardiogram (ECG). This breakthrough could transform the diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias and heart failure.

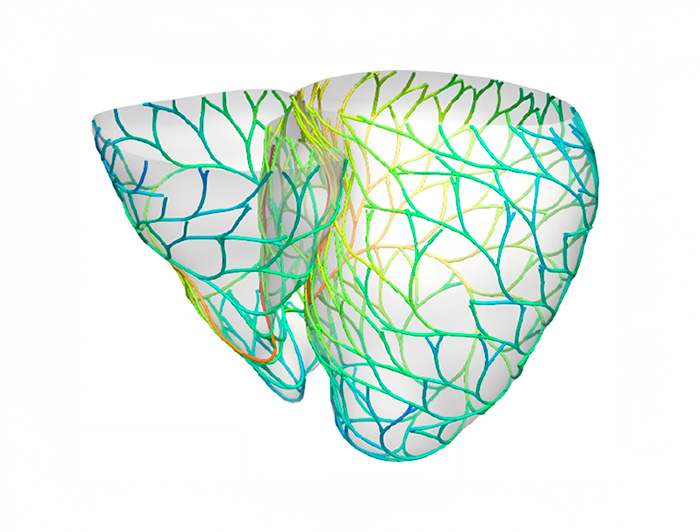

photo_camera The Purkinje network, the heart’s electrical conduction system. (Image: Francisco Sahli)

Cardiovascular diseases claim more than 19 million lives every year worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. In Chile, they are the leading cause of death, responsible for nearly 30,000 deaths annually—29% of all fatalities—according to 2022 data from the Department of Health Statistics and Information (DEIS). These conditions cost the Chilean healthcare system an estimated $1.7 billion each year, even though up to 80% of cases could be prevented by addressing risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.

To tackle this challenge, a team from the Millennium Institute for Intelligent Healthcare Engineering (iHEALTH) developed a computational model that digitally reconstructs the Purkinje network—the heart’s electrical conduction system—using only a standard ECG.

The research, published in Medical Image Analysis, is led by Francisco Sahli, professor at the School of Engineering and the Institute of Biological and Medical Engineering, and principal investigator at iHEALTH. The project combines artificial intelligence, advanced cardiac modeling, and probabilistic analysis to create what specialists call a “digital twin” of the heart—a tool that could revolutionize the diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias and heart failure.

Building the Model

The roots of this research go back a decade, when Sahli developed an algorithm during his doctoral studies to generate realistic models of the human Purkinje network. “The initial model was functional, but one major challenge remained: manually adjusting parameters to match an individual patient’s physiology. This limitation motivated me to find a way to automate the process,” he explains.

After years of research and collaborations—including with a researcher from the University of Trento—Sahli developed an effective method. “The final model required a complete overhaul of the original design and the integration of advanced AI and optimization techniques,” he says.

The development took time: roughly seven years for conceptual refinement and an additional two years for full implementation.

A Vital Structure

The Purkinje network synchronizes the heart’s contractions, but until now, fully visualizing it in patients required invasive procedures. “Our approach makes it possible to create a personalized digital representation of this network using only non-invasive data like ECGs. This opens the door to customized treatments for arrhythmias and heart failure,” Sahli notes.

The model also simulates how the heart would respond to therapies such as pacemaker implantation before the procedure actually takes place. In trials with real patients, it successfully detected abnormal electrical activity, reducing the need for invasive diagnostic tests.

“It’s like having a detailed map of each patient’s cardiac wiring. This could help optimize pacemaker electrode placement and anticipate complications before they occur,” Sahli adds.

The Team and Next Steps

The research team consisted of four members. Sahli, together with Simone Pezzuto from the University of Trento, carried out most of the initial code development. They were joined by an Universidad de Chile intern and a research engineer with a Master’s degree from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile—both of whom are now pursuing doctoral studies in Europe.

The next challenge is to drastically speed up the model’s computation. “Right now, personalizing the model for a single patient takes about a day—far too long for clinical use,” Sahli explains. “Our long-term vision is near real-time personalization: a patient gets an ECG, and within one or two minutes the model is ready, giving clinicians an immediate decision-making tool. Once we achieve that computational efficiency, our next step will be large-scale clinical validation,” he concludes.