First Instrument to Unlock the Secrets of Fog

For more than a decade, Chilean architect and artist Mauricio Lacrampette has been leading a project at the Atacama UC Station that fuses technology, art, and science. Today, a laser that projects a sheet of light can expose the inner structure and turbulence patterns of the camanchaca—a breakthrough that has led to the creation of the world’s first interactive fog observatory.

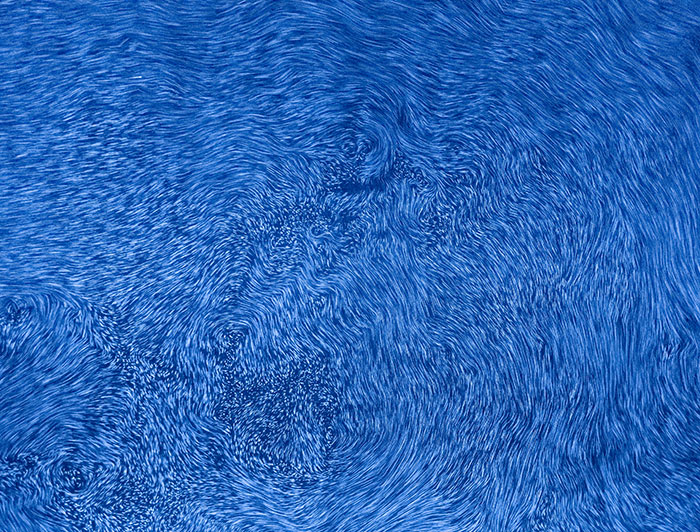

photo_camera The KMNCHK ObsLam, installed at the Atacama UC Station, is the result of a decade of research, integrating autonomous solar power, a high-powered laser, and a local connectivity system. (Photo credit: Mauricio Lacrampette)

At night in the Atacama Desert, when temperatures plummet, a dense fog known as camanchaca drifts in from the Pacific Ocean, reducing visibility to just a few meters. Amid that darkness, a blue laser casts a sheet of light across the mist, exposing— for the first time—its internal structure and turbulence patterns, normally hidden from the naked eye.

This almost science-fiction-like scene is the result of a decade of research led by Chilean architect and artist Mauricio Lacrampette at the Atacama UC Station, in Alto Patache, Tarapacá Region.

Here—an oasis of fog 65 kilometers south of Iquique—researchers from diverse fields converge, creating a rare hub of transdisciplinary dialogue where pioneering projects at the intersection of art and science take shape. The work has advanced our understanding of coastal fog, a phenomenon that for millennia has been one of the few sources of water in the desert, while positioning the station as a global reference point for research on the subject.

The camanchaca—once harnessed by the region’s original inhabitants—is a unique coastal fog created when the desert’s hot air meets the Pacific’s cold currents, producing a mist that can extend for hundreds of kilometers and rise as high as a thousand meters.

A Serendipitous Discovery

In 2013, Chile’s National Council for Culture and the Arts, together with the UC Chile Master’s in Architecture program and the UC Chile Institute of Geography, launched an artist residency at the Atacama UC Station. The residency came with two conditions: the project had to work with the camanchaca and incorporate new technological media.

“At that time, no one in Chile had used a laser in an artistic context,” recalls Lacrampette. “It was difficult to find laser pointers powerful enough for the beam to be visible. But I was already experimenting with mirrors and lasers, and this residency was the perfect opportunity to try it on a larger scale—outdoors, and with fog.”

Working on a shoestring budget, he cobbled together his first machine using a school desk, a solar panel, motorcycle batteries, and modified laser pointers wired to a photovoltaic sensor. The concept was simple but clever: during the day, the system stored solar energy; at night, when the fog rolled in, the lasers switched on automatically.

The result exceeded all expectations—what the artist calls “a serendipitous discovery.” Six mirrors arranged within a 300-meter radius reflected the laser beams into luminous geometries that interacted with the fog in unpredictable ways. “It felt as though the machine had merged with natural cycles,” he explains. “You couldn’t tell where the artificial ended and the natural began—the lasers ran on sunlight transformed into light, blending seamlessly into the landscape.”

Scanning the Invisible

That first project, which Lacrampette named Medium, launched a new line of research. He noticed that when laser beams penetrated the fog, they revealed fluxes of density and motion invisible to the human eye. "I realized that if I could turn the beam into a sheet of light, I could capture a cross-section and see the full pattern of the air currents," he recalls.

The idea took shape six years later. In 2019, he returned to Alto Patache with a multidisciplinary team and more advanced equipment. Together with filmmaker Sebastián Arriagada and anthropologist Felipe Cisternas, he developed the KMNCHK ScanLab, a portable laboratory designed to “scan” the internal structure of the camanchaca.

Their method was painstaking. Each night when the weather was favorable, they carried equipment across the desert, hunting for fog. Upon finding one, they set up the laser, transformed it into a vertical sheet of light, and photographed cross-sections every second for a full minute. Over two weeks, they captured more than 600 unique scans.

Each image revealed unprecedented data: the speed of internal currents, turbulence patterns, and fog density at different altitudes. The collaborative environment of Alto Patache enhanced the research, as daily discussions with other scientists continually enriched the project.

Pablo Osses, director of the Atacama UC Station and professor at the Institute of Geography, explains: “The station is important because it brings science and art together, creating a space where cross-disciplinary projects can emerge.” He adds that Lacrampette’s work draws directly from meteorological stations and climatology methods, building a genuine bridge between art and science.

Global Scientific Recognition

The results were so groundbreaking that they drew international attention. In 2020, the project was selected for Festival Ars Electronica in Austria, the world’s leading electronic arts festival. Amid the pandemic, thanks to support from the interschool UC Chile–UCH initiative PRISMA Art and Science, led by Valentina Serrati, the team secured funding to return to Alto Patache and produce new material for the festival.

During that second visit, they achieved a technical milestone: a nine-minute long-take recording that captured the turbulence of the camanchaca in motion and in real time—the first time the phenomenon had ever been documented at such high spatial and temporal resolution.

The World’s First Fog Observatory

The success of earlier projects inspired an even more ambitious idea: a permanent observatory where visitors could experience fog being “sliced” by laser light. "Seeing the inner life of the camanchaca in motion is indescribable," Lacrampette says. "It was too extraordinary to keep to ourselves."

Installed permanently at Alto Patache in 2024, the KMNCHK ObsLam became the world’s first interactive fog observatory. The system uses a 10-watt laser projecting a sheet of light up to 10 kilometers long, cutting through the fog and exposing its structure in real time. Visitors can watch the phenomenon with the naked eye or connect via their smartphones to capture their own fog scans.

Milton Avilés, regional coordinator of the Atacama UC Station, witnessed the project’s evolution firsthand. “When I first arrived, they were testing with a very thin laser—nothing compared to what they have now. Even so, it was already striking to watch,” he recalls of his first field visit.

The installation of the permanent observatory in 2024 marked a milestone for the station. “It was moving to see them assemble it piece by piece, until they powered it on and tested it,” he adds. The surprise came when “they left and told me it would remain as a gift for the station.”

Rather than relying on expensive imported equipment, Lacrampette designed “situated technology” using locally accessible components: Raspberry Pi microprocessors, 3D-printed parts, and repurposed metal pipes. This approach ensures the system is repairable and adaptable to the station’s needs.

The result is a one-of-a-kind instrument that reveals fog in all its detail, right in Alto Patache’s fog oasis—transforming an invisible phenomenon into a striking visual experience open to every visitor.

Technological Innovation in Extreme Conditions

Building the observatory required overcoming significant technical challenges. The system had to operate autonomously in one of the harshest environments on Earth, where daytime and nighttime temperatures can vary more than 40 degrees, while in the coastal desert, this variation is between 6 and 20 degrees, and winds can exceed 80 kilometers per hour.

The solution combined multiple technologies: a solar energy system powerful enough to run both a high-intensity laser and a microcomputer; a 3D-printed housing engineered to resist salt corrosion; and a connectivity system that creates a local Wi-Fi network, allowing users to scan the fog directly from their mobile devices. The network was developed by software engineer Sebastián De Andraca.

The Atacama Desert presents unique challenges for electronics: intense UV radiation, sudden humidity changes caused by the fog, and airborne salt particles that corrode metals. Each issue demanded custom solutions specifically designed for these extreme conditions.

The assembly of the observatory brought together a multidisciplinary team: architect Dannery Elizondo, a specialist in digital manufacturing who produced the 3D-printed components; designers Lucas Margotta and Diego Gajardo (Sistema Simple Studio); and Eduardo Tobar, a metallurgist renowned in the Chilean art community, who crafted the metal structure with laboratory-level precision.

A Tool for the Future

Lacrampette’s research has created a unique model of collaboration between art and science. Each scan is georeferenced with GPS and linked to meteorological data from Alto Patache weather stations, producing a database with both artistic and scientific value.

His machines act as “portals to the unseen,” revealing invisible forces that shape the landscape and offering new ways to understand natural phenomena. In this framework, the camanchaca becomes an “interface,” mediating complex relationships among the ocean, atmosphere, solar radiation, microorganisms, desert vegetation—and now, human technology.

Today, the KMNCHK ObsLam operates permanently in Alto Patache, accessible to researchers, students, and visitors who coordinate access with the station. The project continues to grow, currently featured at the Regional Museum of Iquique, while educational and outreach initiatives explore establishing similar observatories in fog-prone regions worldwide.

The Alto Patache observatory showcases how technology can be thoughtfully integrated into the natural landscape—and how transdisciplinary collaboration can produce results no single field could achieve alone.